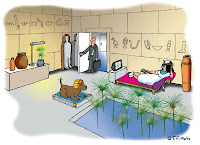

In recent years, ornamental grasses have become de rigueur for most modern garden designs. They are graceful, tall, and elegant – rather much the Audrey Hepburn of horticulture. But how can we translate this vertical effect to our indoor gardening environment? The solution comes replete with a rich and stunning history dating back to the ancient Nile, Pharaohs, Egyptian gods, and Moses in the bulrushes. Welcome to papyrus, one of the most important plants in early human civilization.

In recent years, ornamental grasses have become de rigueur for most modern garden designs. They are graceful, tall, and elegant – rather much the Audrey Hepburn of horticulture. But how can we translate this vertical effect to our indoor gardening environment? The solution comes replete with a rich and stunning history dating back to the ancient Nile, Pharaohs, Egyptian gods, and Moses in the bulrushes. Welcome to papyrus, one of the most important plants in early human civilization.Papyrus (Cyperus papyrus), is undoubtedly the most famous member of the genus Cyperus (kupeiros is Greek for sedge), which is comprised of some 4,000 to 5,000 species, several of which are well-suited for indoor and outdoor pond gardens. The species name papyrus derives from the Egyptian word meaning “that which belongs to the house,” where house alludes to the ancient ruling body or bureaucracy.

Papyrus is, of course, the source for our word paper, and was also the plant used to produce sheets of paper for thousands of years, beginning as early as 4,000 BC. In fact, a thriving and vital trade existed for this writing material until about the third century AD, when it was found easier to produce paper from plant pulp, in a process introduced into the Middle East from China via Arab traders. Papyrus-paper also faced competition from Europe and the Near East in the form of parchment or vellum, which was made from animal skins, such as calf or sheep (hence getting your diploma or “sheepskin”). Papyrus continued to be manufactured and used in ever-decreasing amounts until the 11th century.

Interestingly, the plant itself all but disappeared from Egypt during the 20th century, due to dams on the Nile and other unsustainable practices. The plants were reintroduced into the area around Cairo from thriving native plant stock in Ethiopia and the Sudan in the late 1960s by Dr. Hassan Ragab, an Egyptian inventor and scientist, who also rediscovered a method for creating papyrus, which has now reemerged as a high-end novelty product and specialty paper.

Papyrus was, however, much more than an everyday paper product. Ancient Egyptians would also use the soft pith of the stem as a foodstuff, cooked and processed like sugar cane, or eaten raw. Ancient pharmacologists, like Galen and Dioscorides, cataloged a wide variety of medicinal uses for infusions made from the plant. Egyptians also harvested and dried the woody rhizomes and culms to use as a fuel – whose ashes were also medicinal! Garlands were woven from the graceful flower heads to adorn the shrines of the gods, and for funeral observances. The stylized representation of the papyrus inflorescence, or umbel, is a central motif in the art of the period, akin to the lotus motif in Eastern art. Fibrous strands taken from the stem of the plant were used to weave sandals, ropes, plaited fans, mats, wrapping materials, and to produce, oh yes, baskets.

Lest we forget, the basket into which Mariam and Jochebed placed the infant Moses to escape the infanticide decree of Pharaoh was woven from papyrus stems. And, as you think of sister Mariam watching the basket float along the Nile and nestle into the bulrushes, keep in mind that bulrush is but another common name for papyrus. Holy Moses!

Today, papyrus can find a ready welcome far from the subtropical banks of the Nile, especially as there are closely related species of sedge which can readily fit into a water garden, pond, or even into an attractive indoor container. Actually, the true papyrus species is overwhelming, and might be more bulrush than you can handle. Under ideal conditions, Cyperus papyrus can grow between 12 and 15 feet tall, with stems approaching six inches in diameter, although most gardeners report that indoors the plant only reaches eight feet. Still, that might be a bit much for the average family room. And don’t forget that all of the papyrus-like species originated in tropical and subtropical climes, and will need to be relocated indoors before the first frost.

A species suitable for the average backyard water feature is dwarf papyrus or miniature cyperus (Cyperus prolifer), which will stay upright and well-ordered at no more than 12 to 36 inches. Like most Cyperus, the plant thrives in full sun and likes to sit in water. Pretty ideal, having a plant that cannot be overwatered! This species can also take light to partial shade in the yard, or will purr happily in a sunny indoor window.

Pygmy Egyptian papyrus (C. haspan) has a sparkling appearance much like a bright green feather duster. It will top out at about 18 inches, and feels at home in a pot filled with a rich, loose soil mix, which is then placed in a second larger container filled with water – or set into an outdoor pond.

My personal favorite Cyperus species actually hails from Madagascar, and while it bears some overall resemblance to papyrus, its leaves are thicker and lie in a flat plane, which easily led to its common name, umbrella plant (C. alternifolius).

Umbrella plant can grow to five feet or more indoors, and slightly larger outdoors, although three to five feet is more common. Another sedge, it has a triangular stem, whose shape lends structure support to keep the stem upright in strong winds, perhaps faring better than the average umbrella. It also loves to sit in water day after day.

In fact, many of us who fancy the plant actually grow it in nothing more than a cachepot or sealed container filled with water, and lined with rocks on the bottom to help stabilize plant roots. In this hydroponic setting, it’s important to fertilize somewhat regularly, especially during active growing and flowering periods. But don’t mind the flowers: nothing much exciting there, mostly a bland, tan, oat-shaped affair.

Like most sedges, umbrella plants can be propagated by dividing the substantial root masses or clumps of rhizomes, keeping the outer, younger sections for replanting, and composting the older core. Although a much more entertaining method, of which I have not tired in more than 20 years, calls for cutting off the top six inches of a stem of the plant, leaves and all, and inverting the whole into a glass or vase of water. After a few weeks, roots will form around the junction of leaves and stem, and new shoots will emerge growing up, out of the water. When well-established, carefully plant the rooted cutting into a loose soil mix and keep well watered – or immersed. You can also continue to let the plant grow in water alone.

For the record, several plants gracing the bookcases in my office are descendants from several cuttings given to me in 1979. They have, over the years, produced huge clumps of plants for my rooftop garden, and smaller, discrete potted specimens for windowsills. Scores have been propagated and given to friends and curious visitors. And the tradition lives on.

Like the Egyptian papyrus alternatives, umbrella plants are available in compact and dwarf varieties, such as sparkler grass (C. alternifolius gracilis) under 18 inches with delicate, narrow leaves, as well as in a related variegated form (C. diffusus variegatus), where both leaves and stems are striped with a touch of creamy white against a wide, light green leaf.

Whether you’re striking out to honor Osiris, or print your own Book of the Dead on homemade papyrus, or maybe just add a little excitement to your parlor window with a dwarf ‘Nana’ umbrella plant, you can find just the right plant through online sources year-round, while many fine garden centers sell potted specimens in their water garden section.

Copyright 2008, Joseph M. Keyser